History of the Development of the Neighborhoods in Rockaway, Queens, NYC.

This week the NYC City Council passed the “City of Yes” housing law, paving the way for an estimated 80,000 new homes to be built over the next 15 years to address the ongoing housing crisis. Despite this major step forward for our city, areas of NYC retain their exclusivity through zoning laws and historical legacy, like in the areas of Belle Harbor and Neponsit in Rockaway, Queens. Fierce opposition from residents and community groups (like the Belle Harbor Property Owners Association) in this area of Queens (and similar communities with historically restrictive zoning) resulted in a watered-down version of what housing advocates hoped would pass by the council. The version of the “City of Yes” law that passed aims to preserve the unique characteristics of communities like Belle Harbor and Neponsit, where zoning has only allowed single-family homes for decades. But how did this area become so exclusive in the first place? What happened throughout history to give these communities their “character”? To understand this, we have to look back to the communities’ founding and policies, both formal and informal, that shaped the development of the Rockaways.

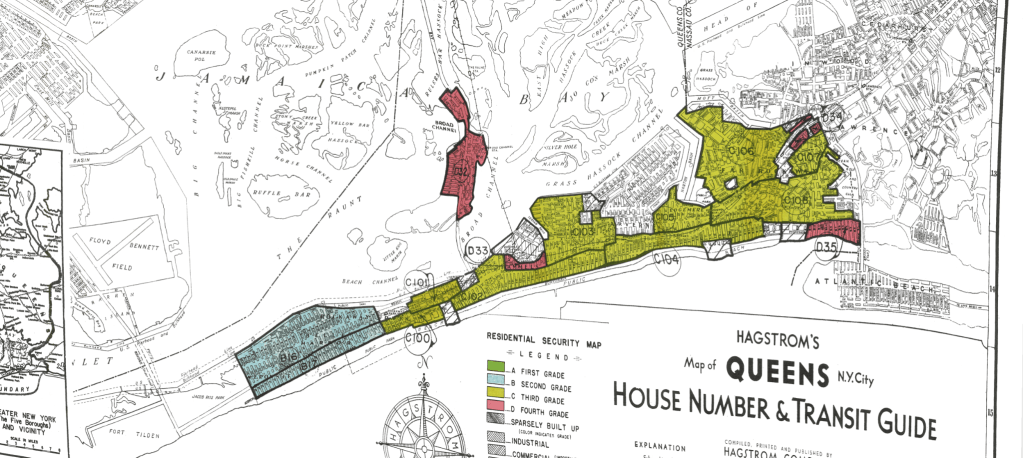

Firstly, we must examine the impact of the federal government’s policies on neighborhood development through the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation’s (HOLC) color-coded maps of the 1930s (through a process known as redlining) to understand the disparity seen across the Rockaways. Redlining produced maps for every neighborhood in the country, dividing neighborhoods into 4 categories based on “perceived investment risk:”

- Green (Best): areas considered highly desirable (often white and affluent, wealthy, neighborhoods)

- Blue (Still Desirable): areas considered good but significantly less affluent)

- Yellow (Definitely Declining): areas considered risky for investment, often with working-class residents and/or older infrastructure (often with a large immigrant population).

- Red (Hazardous): neighborhoods deemed the riskiest, often with significant populations of Black, immigrant, or low-income residents (outlined in red, where the term “redlining” comes from) and/or older infrastructure.

The green and blue designations were most desirable, and the yellow and red regions were designated too risky for investment. As a result, the people living in the yellow and red regions were systematically denied mortgages, businesses did not invest here, and it was used to justify ‘slum clearance’ projects (a hallmark of the Robert Moses era in the quest for ‘urban renewal’). These designations were racist & classist and based on the demographics of the people who lived in these areas at the time.

Here is how redlining played out on the Rockaway Penninsula by the HOLC in 1938:

To view an interactive map of redlined areas across NYC, click here.

As you can see on the map, large swaths of the Rockaways were deemed to be Grade C (Yellow, Definitely Declining). The main reasons for this were the significant Irish and Jewish populations and signs of Black migration into the area, as the HOLC explicitly considered these shifts as negative indicators for property values, using terms like “infiltration” to describe this shift. Other reasons for the low ratings were that Far Rockaway was the oldest community on the peninsula, containing both multi-family and single-family dwellings, so the housing infrastructure was viewed as lesser by evaluators compared to the more recently developed neighborhoods of mostly single-family homes. Some of Rockaway was also given Grade D or “hazardous” rating in the Hammels neighborhood, as well as parts of Far Rockaway, primarily because of its mix of Black, immigrant and Jewish people residing in this area. The impact of redlining is still felt today through economic decline, segregation, divestment, and stigmatization of these areas.

(Note: The community of Breezy Point is not included because it wasn’t formally developed as a cooperative until later in the 1960s. Much can be said about Breezy, but the focus for this post is on the other neighborhoods of Rockaway. To read more about how Breezy maintains its exclusivity, read A Gated Community in NYC Where Trump Flags Fly).

All of Rockaway was designated in Grade C (Yellow) “definitely declining” or Grade D (Red) “hazardous,” except for certain parts of Rockaway Park that were given Grabe B (Blue) or “still desirable,” starting from Beach 117th street to Beach 149th Street. These neighborhoods (Belle Harbor starting on Beach 126th Street, and Neponsit starting on Beach 142nd Street) were secluded from their inception; this section of Rockaway is not connected to the subway (which ends at Beach 116th Street) and was developed after the other neighborhoods on the peninsula. It was made up of mainly Irish and Jewish immigrant families, and the zoning laws from the beginning only allowed single-family homes.

HOLC evaluators explicitly favored neighborhoods that were racially homogeneous and white. Belle Harbor and Neponsit were overwhelmingly white and excluded Black and minority families through a combination of formal and informal practices, including restrictive covenants and community pressure. The absence of Black or other minority residents aligned with HOLC’s discriminatory standards. The houses in this area were also newer and made of higher-grade materials, making it more attractive to evaluators at the HOLC.

Belle Harbor, was founded in 1905 by real estate developer Frederick J. Lancaster. His vision was to create a high-end residential community along the Atlantic Ocean, marketed as a peaceful, escape from urban life. It was advertised as a “high-class residential district,” attracting affluent families from Manhattan and Brooklyn.

Neponsit was the last community to be developed, with advertisements like the one above explicitly stating “it’s a restricted community for refined people.”

Both Belle Harbor and Neponsit have a racial demographic make-up of 0% African American, with Belle Harbor having 87% white, 10% Hispanic and 3% Asian making up the rest, and Neponsit having 89% white, 8% Hispanic, 2% Two or More Races and 1% Asia (Source).

Given this history of how the Rockaways were developed, the impact of redlining, and the informal and formal practices to keep these sections for white residents only, I don’t think there is much of a defense for keeping the “character” of these communities intact via restrictive zoning laws that uphold these impacts today. The “City of Yes” spared these communities by allowing the parking requirements for new developments to stand as they are, as well as upholding the restrictive zoning that has led to the segregation we see here today.

I plan to unpack the “City of Yes” law more in future blog posts, so follow along for more if you found this post interesting!

If you want to learn more about the history and impact of redlining, read the book titled The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein.

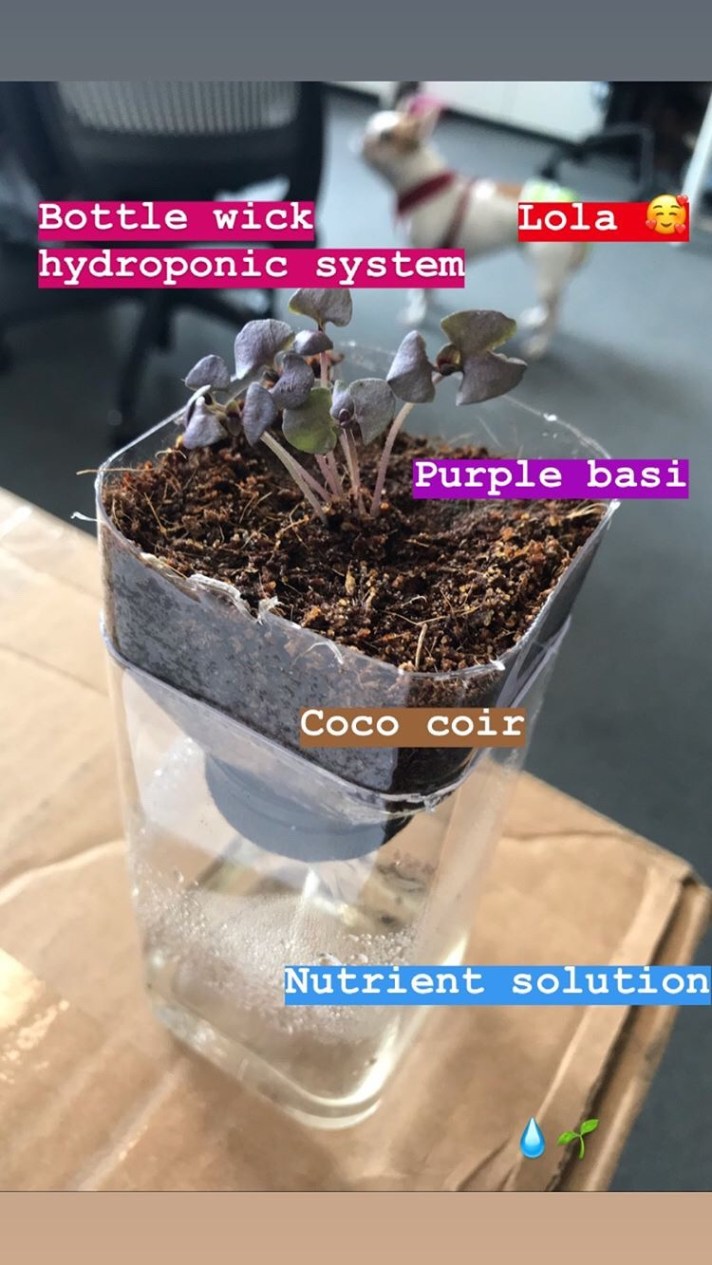

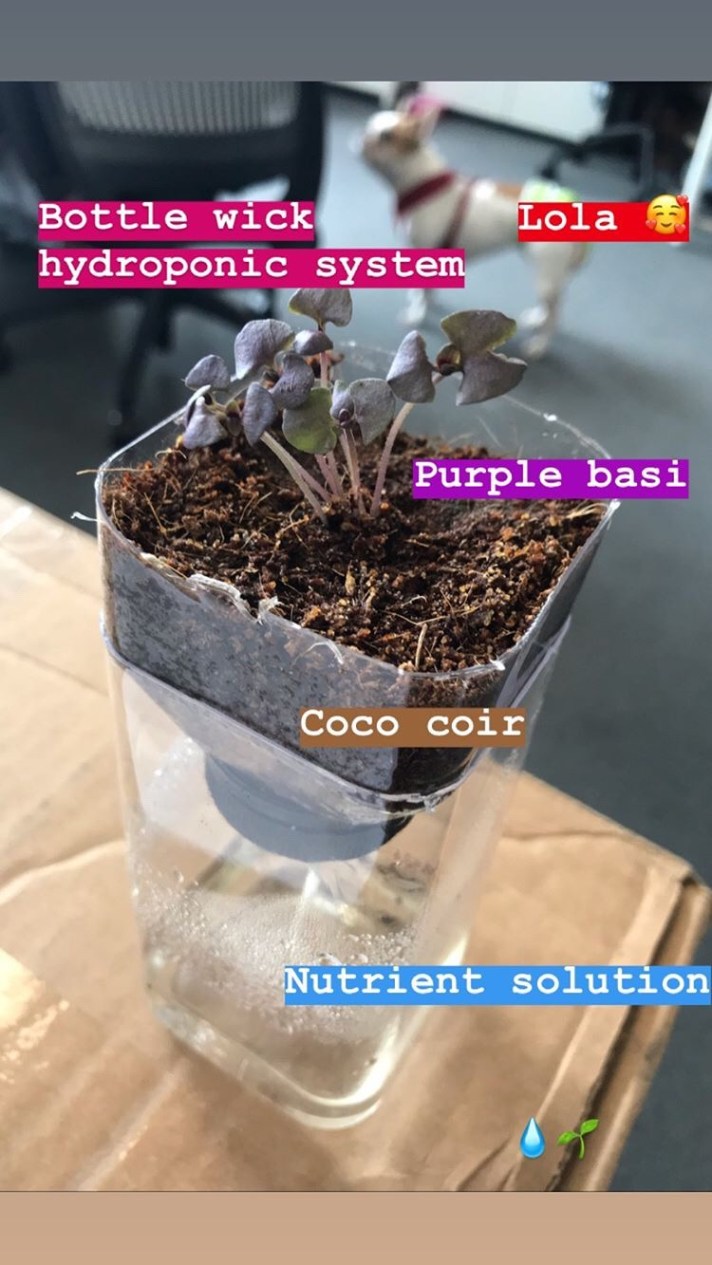

@Hydroponics.NYC

@Hydroponics.NYC

Hydroponic Wick Bottle Systems made by middle schoolers in Brownsville, Brooklyn with Teens for Food Justice. @Hydroponics.NYC

Hydroponic Wick Bottle Systems made by middle schoolers in Brownsville, Brooklyn with Teens for Food Justice. @Hydroponics.NYC Purple Basil.

Purple Basil.

*Note the existing pipeline was pushed through and built after Hurricane Sandy, when local residents were preoccupied with the rebuilding of their homes and communities (Source: NYC Surfrider Foundation).

*Note the existing pipeline was pushed through and built after Hurricane Sandy, when local residents were preoccupied with the rebuilding of their homes and communities (Source: NYC Surfrider Foundation). Fort Tilden, NYC. @hydroponics.mh

Fort Tilden, NYC. @hydroponics.mh An oystercatcher in Rockaway Beach, NYC. @hydroponics.mh

An oystercatcher in Rockaway Beach, NYC. @hydroponics.mh Jacob Riis Park @hydroponics.mh

Jacob Riis Park @hydroponics.mh “Exploring with my Nana at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, NYC, on 12/30/13.” @hydroponics.mh

“Exploring with my Nana at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, NYC, on 12/30/13.” @hydroponics.mh Jacob Riis Park. @hydroponics.mh

Jacob Riis Park. @hydroponics.mh