The simplest answer to this question, for me, is a clear and unequivocal yes (This is also my second post about GMOs, so I clearly believe we should be, at the very least, aware of the issues surrounding the topic). Recent reports from news media have questioned whether or not food products containing GMOs (genetically modified organisms) should be labeled as such, so that consumers can choose if they will, or will not, buy the product. This has sparked a serious debate concerning the safety GMOs in our food system. Although some people argue against the labeling of GMOs for causing unnecessary fear surrounding the safety of these products, there is legitimate reason to approach GMO products with caution for political, social, and environmental reasons.

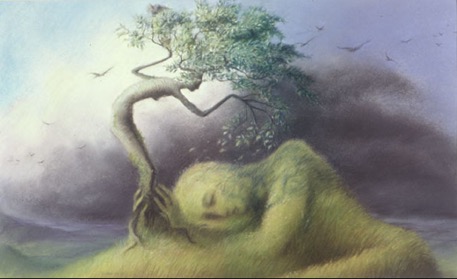

The most important reason to oppose the use of GMO crops is the environmental consequences from the form of agriculture that is necessary to grow these crops: monoculture systems. In short, monoculture farmers plant only one crop in a given area to maximize the yield of this crop. When a farmer choses (or is economically forced) to grow GMO crops (like corn, cotton, or soy), they adopt a monoculture style of growth to maximize the yield of the crop. One reason for planting all of the same variety of plant in the same area is that it makes it easier for the farmer to spray pesticides without killing the other crops (Since most GMO crops are designed to withstand the poisonous nature of pesticides, they will not perish in the presence of excessive pesticide use). Moreover, planting monocultures makes your farm less resilient because if the crop fails, there is no other crop variety to fall back on for food. If farmers cannot produce and sell enough of their one crop, then they cannot feed themselves. Still, it is more efficient to grow GMO crops in monocultures under the current economic system. Large seed companies are then able to sell farmers seeds and pesticides, often with the promise of increased yields.

The argument of increased crop yield is used all the time in favor of the use of GMOs, but it is simply not true that GMOs yield more food. For example, in India, GMO cotton was sold to small farmers with the promise that their yields would be higher than organic, traditional farming methods (Small farmers account for about 80 percent of food production in India). Today, about 95 percent of the cotton grown in India is a Monsanto GMO product. It is true that cotton yields increased with the introduction of GMO crops in India because people started to just grow cotton instead of maintaining their traditional polyculture system of planting cotton alongside other nutritious food crops. Overall food output has not increased because of the monoculture systems implemented by GMO cotton crops in India. The result was an influx in cotton production and a decrease in the production of nutritious crops that feed people. Now, this would be a good thing if farmers were selling their cotton and receiving enough money to purchase what they need to eat, but this is not the case. Agriculture output decreased and yield of the specific cotton crop increased. People do not eat cotton and increased supply means a decrease in the price of cotton. This caused enormous economic pressure on India’s small farmers because they were now indebted to buying seed and pesticides from these companies, like Monsanto.

One crucial social aspect of this issue to understand is that farmers in the past had no need to buy seed from anyone. Nature provided seed to the farmers (specifically women in India assumed the role of traditional seed saving techniques). Seeds are the source of life, but large companies have now patented life and made it illegal for farmers to save their seeds for the next growing season. This created a cycle of planting and buying expensive GMO seeds for many small farmers in India. When their crops did not produce enough to sustain the farmers, there was a stark increase in suicides among farmers in India since 1997 and 1998. Granted, there were suicides among farmers before this date (as there are unfortunately in every society), but there was a clear increase in the number of suicides among farmers when this economic pressure of debt became greater with the use of GMOs and the accompanying pesticides. (Vandana Shiva is an inspirational advocate against the use of GMOs, specifically in India but also around the world, and she writes/speaks extensively on the topic). Putting all your eggs in one basket is never a good idea, especially when you are an economically vulnerable small farmer.

Similarly, in the United States, farmers receive subsidies from the government to grow corn (which is dominantly GMO corn), and most of this crop is turned into ethanol for fuel. Less food is being produced on these large monoculture farms because food is now a commodity to be sold efficiently in the global market. If the government is going to pay you to grow fuel instead of food, you will grow GMO corn for fuel because of the economic gain. There is still a huge social and environmental cost. As Vandana Shiva (environmental activist and physicist) puts it, if we were growing food for nourishment, then we would maximize nutrition by planting biodiverse polyculture agricultural systems. Instead, we are growing food to maximize profits, which supports a monoculture model of agricultural production.

Furthermore, there are political and legal consequences to the debate around GMO use in agriculture. As I mentioned earlier, the contracts small farmers enter into with large seed companies, like Monsanto, legally restrict farmers from saving their seeds. They are forbidden from planting these seeds again, and they cannot share seeds with anyone. In the United States, there are many cases of farmers who were sued by Monsanto for illegally growing their patented seeds, and often these farmers do not even know that they are growing GMO crops because of the nature of pollination. If your neighbor decides to grow GMO corn, your crop of organic corn is at risk of being contaminated by patented GMO pollen from the neighboring crop because corn is pollinated by the wind. You then are vulnerable to being sued by Monsanto for stealing their patented seed. The concept of having ownership over life is a new one, and it has allowed Monsanto, and other companies, to put small, organic farmers out of business. Once the small, organic farmer can no longer afford their land after litigation, the neighboring GMO farm is eager and ready to take over the farmland to plant more GMO crops.

Moreover, the enormous backlash against labeling GMO products in the United States is serious political problem. With the upcoming presidential reelection campaigns in full swing in the United States, we can see the corrupting influence money has on the political process. (Recent polls have Donald Trump leading the race for the Republican nomination, even after his racist and insensitive comments about Mexicans. Do I need to explain the power of money in politics any further?) If we allow seed production and dispersal to be controlled by large corporations, politicians will undoubtedly be influenced by these companies when implementing food policy. There is no way your average citizen in the United States can compete with Monsanto lobbyists. The result is that these companies will have the access to politicians that they need to create the laws necessary to perpetuate the cycle of control over seed dispersal and secrecy surrounding products that contain GMOs. Currently, citizens of the United States do not even have the right to know if they are consuming GMO products because GMOs are not labeled on packaging. There is even a push by some politicians to make it illegal to label GMO products for what they are: GMOs. If there is nothing wrong with GMOs, why not label them?

Although many people believe the future of GMOs provides us with great hope for innovation and higher efficiency in food production, we must consider the environmental, social, and political implications of GMOs. The high cost of non-renewable seeds for small farmers, the increased pesticide use on GMO crops, and the huge political influence companies have on politics are a few great reasons to be concerned about the production and consumption of GMOs. Moreover, traditional selective breeding methods can be extremely effective at adapting a certain plant species to a specific region, and this has tremendous potential for helping farmers deal with the changing climate. Small farmers still feed most of the world. Rather than looking to large corporations to solve the problem of food insecurity, we should place higher value on the traditional knowledge of ecological-minded small farmers around the world.

To see Vandana Shiva answer some hard questions surrounding GMOs in a BBC interview watch: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vbIQF72IDuw

47.473352

-0.555490

@Hydroponics.NYC

@Hydroponics.NYC

Lettuce growing at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan

Lettuce growing at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan Cucumbers and a variety of leafy greens and herbs growing hydroponically by students at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan

Cucumbers and a variety of leafy greens and herbs growing hydroponically by students at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan @matt_horgan

@matt_horgan Students participate in a cooking challenge to create a veggie burger, chocolate avocado pudding, and pasta salad. (Secret ingredient: parsley grown in the schools hydroponic farm) @matt_horgan

Students participate in a cooking challenge to create a veggie burger, chocolate avocado pudding, and pasta salad. (Secret ingredient: parsley grown in the schools hydroponic farm) @matt_horgan