How did I become interested in

sustainable food systems?

One of my earliest memories about where my fascination with nature comes from is when I was on my way home from a soccer game with my dad when I was about 8 years old and, as we drove through a long stretch of trees in Broad Channel, I was curious about this place, so I asked my dad if we could stop.

We walked around the trails of this vast marshland, which is a crucial stopping point for migratory birds flying South for the winter. The vastness of this area makes you feel like you are in a truly wild place. This is Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in Broad Channel, Queens, one of only a few national parks in NYC (part of Gateway National Recreation Area). We often would fish on the beach and bay along Rockaway with my dad and mom, so I always had ample time to explore the wildlife in these areas.

Broad Channel, Queens, NYC (photos by me, @matthewgerard_)

Where I grew up, in Belle Harbor (Rockaway Park) located in Queens, NYC, we are surrounded by water on 3 sides (the Atlantic Ocean to the South, Lower New York Bay to the West, and Jamaica Bay to the North).

This map is from the book, Between Ocean and City: The Transformation of Rockaway, New York (2001).

I attended Xaverian High School, an all-boys Catholic school (at that time). With encouragement from my mother as well as my eccentric Spanish teacher in my sophomore year, I applied to be in the International Baccalaureate (IB) diploma program at the school. This led to me taking an IB Environmental Systems class in junior year, changing the way I thought about the world. The teacher presented environmental issues through a systems lens, and I never heard or thought about most of these environmental issues before this class. The seeds were planted for my interest in environmental studies.

Photo: depicts the components of a simple system

But as much as life’s drive comes from our passions and things we love, we are also profoundly shaped by the darker things that are a part of our life.

When my dad was diagnosed with late-stage cancer at the start of my junior year of high school, the pressure of being in an accelerated IB diploma program and navigating his illness felt daunting at times.

I am so grateful to have had amazing teachers along the way who kept me going during this immensely challenging time.

Ultimately my dad passed on a few months before I graduated from high school, on March 12, 2010. Addiction and depression are also a part of my story and began a little before & around this time.

I was also suppressing core elements about my identity at the time, in fear that I could not live a happy life as an openly queer person. It wasn’t long before things became unmanageable, and I saw a doctor for medication to cope with the depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, even doctors can be misguided and easily manipulated, so although this was a temporary and necessary fix for me at the time that allowed me to continue, addiction and depression will reemerge for me later in this story. (I debated putting details of addiction and depression in here, but I think lessening stigmas of all kinds, including around mental illness, is so essential today).

This picture was taken in New Jersey when my sisters and I would go to visit every other weekend for much of my childhood (@matthewgerard_)

I started attending SUNY Binghamton the following Fall 2010, where I would begin on a Pre-med/health major track. After seeing what happened in 2008 with the financial crisis, the health field felt like a safe bet for ‘success’. However, it never felt like I was following my passion in any particular way.

In sophomore year, I decided to take an Environmental 101 class. I was extremely captivated by Dr. Andrus’ lecture on the many issues and root causes of the most pressing environmental issues of our time. I was brought back to when I was passionately activated in high school when I took the IB environmental course, which led to me declaring my major in Environmental Studies at the end of that year.

Photo: During my time at Bing in November 2012, Hurricane Sandy destroyed many areas, including the neighborhood where I grew up. It highlighted for me the importance of studying climate change and sustainable development strategies for building resiliency in our society.

I had the amazing opportunity to attend a trip to Costa Rica to complete a Tropical Ecology course for July during the summer between my sophomore and junior year at Bing. About 15 of us stayed on a site that did not have wifi or cell phone service and was an hour and a half journey to the nearest city center. This experience was invaluable to me and helped me grasp the scope of biodiverse ecosystems that are here on Earth, and gave me an urgent sense to be a part of the environmental movement in some way. It also provided me with an alternate perspective on success, as we were hosted in the community by such welcoming, generous, happy people, but they did not have much in terms of wealth or disposable income.

Dick Andrus discussing the importance of mangrove forest ecosystems (@matthewgerard_)

I was also very lucky to have an influential professor at Bing, Dr. Andrus, who founded the environmental program at the university decades earlier and sparked my interest in that Envi 101 lecture in 2011, and who ran the trips to Costa Rica.

While I was at SUNY Binghamton, I was so grateful to have access to a free psychotherapist on campus named Sefali. She was a tremendous help at convincing me that I could live a happy life as an openly queer person, and she taught me the skills of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that were crucial in me getting off medication in the years to come. As I became more aware of who I was, my voice was activated at my first protest against hydrofracking in NYS (which is thankfully still banned in NYS today).

I graduated from Binghamton in May 2014 with a B.S. in Environmental Studies, however I was not sure what type of job I would ultimately get with this degree because of its broad nature. I decided to apply to graduate schools, in hopes of furthering my education around environmental issues and solutions.

As I waited to hear back from schools, I volunteered with the Vermont Sail Freight Project in the summer following graduation. The goal of this project was to connect Upstate & Vermont farmers with the lower Hudson Valley and NYC to farm goods via sail transportation through NY State’s historic canal lock system. Dr. Andrus’ son, Erik, led the initiative and is primarily a rice farmer and baker in Vergennes, Vermont. I lived on Erik’s farm for a month as we inventoried and coordinated goods to sell from on the 30-foot, volunteer-built barge along the Hudson River.

Erik & Erica’s idyllic farm and home in Vermont (@matthewgerard_)

Loading the cargo onto the barge staring at Lake Champlain (@matthewgerard_)

As our four-to-five-member crew made our way down the Hudson River, I learned so much about sailing terminology and practice, the history of the lock system and NY History, and about our local food system here in and around New York State and volunteerism. It was a ton of work, and I am so grateful for the perspectives gained working on this project.

French documentarians on board the barge as we made our way to the next farmers market in the communities in the Hudson Valley. (not sure what ever came of their footage). (@matthewgerard_)

Picture of NY States Canal System consists of a series of locks connecting different canal segments that make it possible to get from Lake Champlain to the Hudson River. (@matthewgerard_)

On the Vermont trip, I found out I was accepted to a Master’s program at St. Edward’s University in Austin, TX, and another Environmental Science program at Pace University campus in Westchester. I was still not convinced that I wanted to live in NYC, and Westchester sounded a lot like Binghamton to me, so I decided to go to Austin.

The program at St Edward’s University was a Professional Science Master’s degree in Environmental Management and Sustainable Development, and it was one year in Austin, one semester at their sister school, Catholic University of the West (Université Catholique de l’Ouest, UCO) in Angers, France and one-semester doing research in the field of sustainable development to complete a thesis in a place of your choosing.

Photo of me in Austin conducting a research project on measuring community garden output in the City of Austin. (@matthewgerard_)

This is a photo in Wimereux, where we took a field trip during my stay in Angers, France. The master’s program included the study of ecology, sustainable development, and project management, as well as designing and conducting research projects. (@matthewgerard_)

Photo of Tessa and I with the Gamboa Family, who graciously hosted us for several months on the same property that SUNY Binghamton had brought us to back in my undergrad trip to complete a tropical ecology class. (@matthewgerard_)

To complete the master’s program, I returned to the same village in Southwest Costa Rica, and the Gamboa Family hosted my research partner and me. A special thanks to Mari and her family for always being welcoming, and generous and treating us like family during our several-month stay. I am so grateful to be able to have returned to such a unique place for a research project measuring the amount of carbon stored in old-growth and secondary-growth tropical forests.

Tres Piedras is the name of the village where we stayed, located along the Guabo River in rural Southwest Costa Rica. (@matthewgerard_)

As magical of an experience it was living in a tropical forest for 3+ months, conducting research to write my master’s thesis, the experience was equally as painful for me because of a medication that I had been prescribed for going on 6+ years since my dad’s passing was no longer working as intended. The first signs of a tolerance buildup to the medication were evident to me, however, I was managing it still with the help of my doctor. I decided to move to Hawaii with my (ex)boyfriend, who I met in France, and was now starting a graduate program in Honolulu. I had just graduated from my master’s program and was searching for work in the environmental field on the island of Oahu.

A medication, belonging to the class of drugs known as benzodiazepines, used to treat anxiety, began to work less and less over the years as my body gained tolerance to it (a common issue with prolonged use of benzodiazepines). I found myself in a situation of extreme anxiety when living in Honolulu, as the drug worked less and less and when trying to gradually come off numerous times had failed, and with a doctor always quick to up the dose when I complained of symptoms. The dangerous truth is that the majority of people might need these medications for a short time, but they are not intended for long-term use. They also are considered depressants, so depression is inevitable with long-term use. After about 5 months, I moved back to NYC to get support from family as I realized I needed to get off this medication at whatever cost or it would ultimately take my life.

Photo from my time living briefly in Moiliili, Honolulu, Hawaii (@matthewgerard_)

I knew what my issue was: dependency on a medication I’ve built tolerance to and that I’ve tried to stop taking for so long. I was determined to come off of the medication so I checked myself into a rehabilitation facility focusing on substance abuse disorder in Hampton Bays, Long Island for 21 days (after about a week I was able to leave, but I opted to stay because of how jarring coming back to reality was after detox). It was actually extremely important to go through with a medically supervised detox from the amount and duration I had been taking that benzodiazepine; I was at high risk for seizures during these 8 days of pure hell. That decision to go to LICR (Long Island Center for Recovery) truly changed my life and has allowed everything that followed to be possible.

My experience speaks to the need for universal healthcare and taking paid leave. I was still on my mom’s health insurance and I was able to live with her during this time, so this privilege allowed me to take the time I needed to get healthy again.

While living with my mom after the rehab, I was working as a waiter at a local restaurant and attending (Alcoholics Anonymous) AA meetings regularly. I didn’t think I was an alcoholic, but it runs in my family and is also part of the substance use disorders (like addiction), so I felt immense comfort in having a strong sense of community and accountability in working towards the same goal that AA provided to stay sober. Taking the time I needed to get sober was foundational to my future. It is no exaggeration to say I would not be here today if I did not do it.

After 6 months of being sober and having more clarity of purpose in my life, I felt like I could use my education to make a difference in people’s lives as a teacher (like some of my inspirational teachers did for me in my life). I applied to become a public school teacher through the New York City Teaching Fellows program and was accepted to teach summer school in the Summer of 2017. I soon got my first apartment after grad school, living on my own in my neighborhood of Belle Harbor, where I grew up, and the landlord was into urban gardening!

After completing the summer portion of the Teaching Fellows program, I was given a transitional license to be a full-time teacher that Fall, while I took classes at night to get a Master’s degree in Teaching at CUNY Brooklyn College. I taught high school that fall for 3 living environment and 2 AP environmental science classes (about 150 students) at William Cullen Bryant High School. I was soon extremely disillusioned by being a part of the immense system that the NYC Department of Education is and having an unsupportive school environment to navigate it all as a new educator (where constantly evaluating a teacher is viewed as the primary means of support and the school administration does nothing to support teachers in a meaningful way).

I felt I had made the totally wrong decision to become a teacher so fast, and I was totally burnt out. The depression was setting in faster than I’d ever experienced, this time due to environmental factors rather than medication tolerance-induced. I knew the quickest solution was to change my environment and invest the money I had in myself to figure out what to do next.

By December 2017, I resigned from the DOE in one of the toughest decisions I’ve ever made in my life. The students would have been why I stayed because they deserve a quality education, but I realized if I did not make a major change, I would have to go on medication for depression if I stayed in the situation I was in (whether or not this was true or if my feelings were warranted, I carry with me a hesitancy for medications after my experience with the doctor I saw in late teens/early to mid 20’s).

I realize how much of a privilege it was to be able to resign from my position as a public school teacher, and I credit having the savings to my dad who had written into his will that none of the children were to receive any of his life insurance money until we reached the age of 25. I still had enough in savings to take 4-5 month break to pay for my necessities and realize my next steps, both professionally and personally. I did have to work hard to prioritize my own health after I resigned, exercising and eating well to combat my depression over time, as well as focusing more on meditation, yoga, and skill learned in therapy (CBT). I gained a lot spiritually from taking this pause for myself, and I’m so grateful for being granted such a space. I absolutely needed to do these self-care acts daily for some time before they became routine and contributed positively to my well-being in a meaningful way.

Thank you to my family and friends for your grace and support during these years. I am grateful to say I am still counting the days I have sober from my drugs of choice since the rehab stay in 2017 (6+ years and counting).

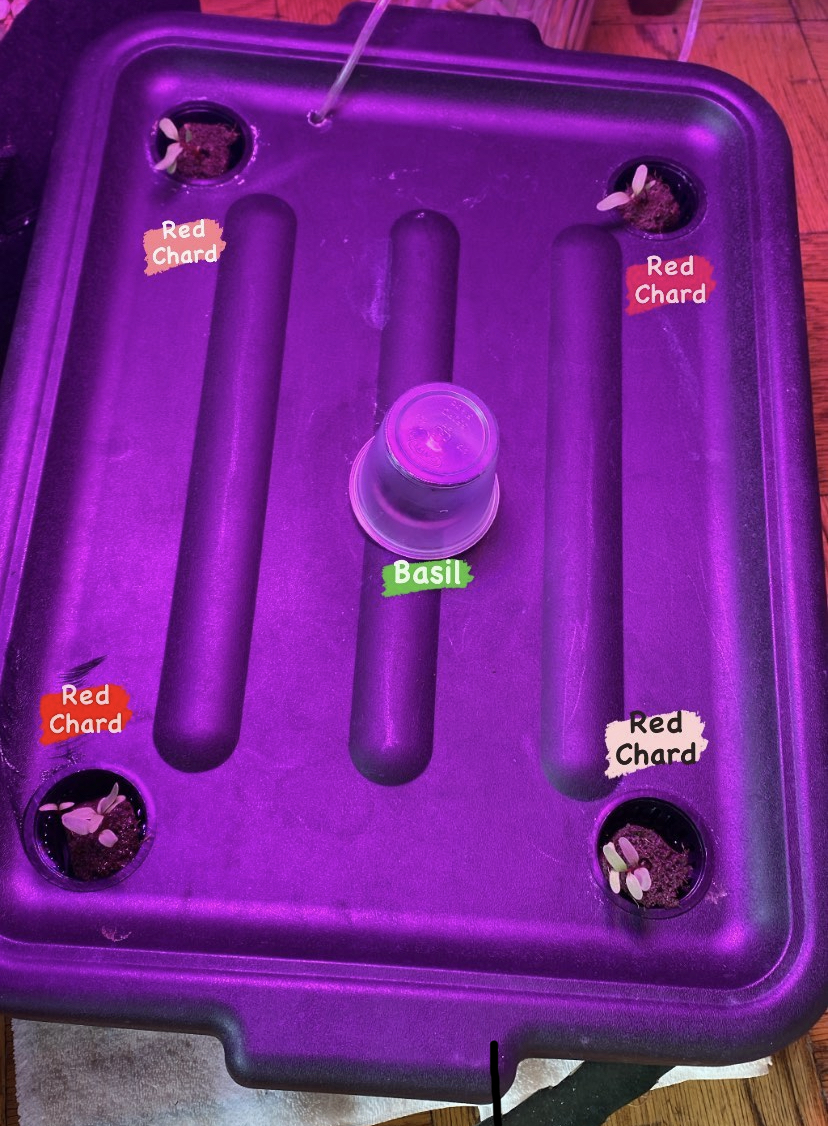

This is a photo of my former landlord’s hydroponic indoor garden she used to grow food for her and her brother. It drew me to my former apartment, which was situated just next door to this room. When I was teaching I had no time to put it in context, but once I had some time, it began to make me wonder:

Who might be working with a hydroponic system to grow food in NYC?

This led me to take a couple of workshops around introductory DIY hydroponic systems with an organization formally known as AgtechX, now merged with Agritecture in the Spring of 2018. I met interesting people who were all working towards building a more sustainable food system right here in NYC. After putting myself out there and networking at these workshops, people pointed me in the right direction of other organizations that worked at the intersection of education and the environment (like GrowNYC and Teens for Food Justice). At this point in my life, I was determined to find a job in the food system, while somehow using my education experience too.

I began working full-time as a farmer’s market manager for GrowNYC at their Greenmarkets and Youthmarkets around NYC, managing one market in Bensonherst, Brooklyn, one in Long Island City, Queens, and one in Morrisania, the Bronx. This job was challenging and rewarding, though I did not need my degrees for the job, it helped me strengthen my sense of place and got me to really love NYC (and wanting to live here long-term).

Photo at Bensonhurst Greenmarket in the Summer of 2018.

At the same time, I drove to the Bronx every Wednesday afternoon in the Spring of 2018 to be a mentor at Teens for Food Justice’s afterschool program. This experience showed me the possibilities for large-scale hydroponic systems to be used in school settings to merge teaching STEM, food justice and advocacy education, and workforce development with high-tech urban farming.

Photo of my first DIY hydroponic system I built from scrap materials after gaining confidence from workshops and Youtube videos, as well as growing inspired by Teens for Food Justice (TFFJ) and my landlord’s systems, built in the Winter of 2018.

During this time (Spring 2018), I was able to return to the rural village where I visited in my undergrad and graduate school and reconnected with Mari and her family. They had a family wedding happening, and I’ll never forget how Mari welcomed me with this LGBTQAI+ mask to make me feel more comfortable. They are very religious here in this part of Costa Rica, so it really meant a lot to me, Love you all ❤

GrowNYC promoted me to be the Operations Coordinator at their flagship Union Square Greenmarket in the Fall of 2018, while I was simultaneously working at Teens for Food Justice part-time as their curriculum writer.

However, after only a few months at my new GrowNYC job, I was offered a full-time position with Teens for Food Justice as their Curriculum Development Coordinator to develop their school day curriculum around hydroponics and train teachers around the curriculum. I decided to leave GrowNYC, even though I loved working with those people, and at that location, I felt I would grow more professionally in the position offered to me at TFFJ. I am so grateful to still be working for them today as their STEM Programming & School Partnership Manager. Both TFFJ and GrowNYC opened my eyes to the inequities between communities right here in NYC.

Please feel free to read about my experience working with TFFJ in my recent blog post highlighting an article written about my work in St Edwards University Magazine.

Thank you all for reading if you made it this far, this blog turned out to be much longer than I anticipated, and I certainly could write a full blog post about each of these chapters of my life.

May you receive it with peace and equanimity,

Matthew (he/they)

@matthewgerard_

This post is dedicated to my dad, who passed away 14 years ago this week from a non-smoking form of lung cancer.

May he rest in love ❤ 3.12.10 ❤

@Hydroponics.NYC

@Hydroponics.NYC

Lettuce growing at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan

Lettuce growing at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan Cucumbers and a variety of leafy greens and herbs growing hydroponically by students at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan

Cucumbers and a variety of leafy greens and herbs growing hydroponically by students at Dewitt Clinton High School in Bronx, NYC. @matt_horgan @matt_horgan

@matt_horgan Students participate in a cooking challenge to create a veggie burger, chocolate avocado pudding, and pasta salad. (Secret ingredient: parsley grown in the schools hydroponic farm) @matt_horgan

Students participate in a cooking challenge to create a veggie burger, chocolate avocado pudding, and pasta salad. (Secret ingredient: parsley grown in the schools hydroponic farm) @matt_horgan